Oil on Canvas; A Huntsman holding a dead Hare, with his Hounds, and a still life of Fowl, Fish and Fruit, by Harmen Steenwijck (Dutch, 1612- after 1656)

Harmen Steenwijck formed part of the generation of artists that flourished during the so-called Dutch Golden Age, which coincided with the independence and consequent economic prosperity of the Dutch Republic across the seventeenth century. Born in Delft in 1612, between 1628 and 1633 Steenwijck trained as a painter in Leiden under his uncle David Bailly (1584-1657), who also taught Harmen’s younger brother Pieter (c. 1615-1666). Upon his return to Delft, he registered with the Guild of St. Luke as a master in 1636. Few additional details have survived about his life, with the exception of a journey to the Dutch East Indies (present day Indonesia) in 1654-55. He was last recorded in Delft the following year.

Steenwijck’s teacher Bailly specialised in portraiture and still-lifes, particularly the type of compositions known as “Vanitas”, images intended to contrast the transience and frailty of worldly pursuits with the everlasting nature of religious faith. Because of their focus on the futility of riches, beauty and knowledge in the face of death, “Vanitas” compositions appealed to patrons as a morally acceptable way of exhibiting the splendour of their collections, encompassing precious objects, jewellery, and wonders from the natural world, which painters duly portrayed with virtuoso rendering of surfaces and materials.

Similarly to his uncle, Steenwijck is chiefly remembered today as a painter of “Vanitas”, his most famous contribution to this genre being a panel now in London’s National Gallery (fig. 1). However, like many still-life artists from the period, Steenwijck also produced interior scenes, ranging from representations of rustic environments such as taverns and country kitchens (Peasant in a kitchen interior with still-life, Musée des Beaux-Arts, Caen) to depictions of more refined spaces, as exemplified by the present canvas. Motifs of game, fish, jugs and fruit are characteristic of his repertoire (Still life with an earthenware jug, fish and fruit, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam; Still life with fruit and plucked duck, Städel Museum, Frankfurt) and are displayed here within the framework of the return from the hunt. On the right, a gentleman in a crimson red robe with golden buttons holds a dead hare, his two hounds standing obediently by his side and his shooting rifle resting on the countertop in the centre. The dogs are described with particular attention to their appearance and fur, which indicates they were painted from life. A large horn is fastened across the young man’s torso, while two smaller powder-horns hang from a wooden ledge above. The lifeless heron next to them, paired with grapes, may hold symbolic significance connected to the Eucharist, while the other items hanging from hooks can be identified as hunting paraphernalia (a powder-bag, nets, and bird cages). Such incorporation of symbolism within a seemingly mundane subject is not usual in art of the Dutch Golden Age, especially within the context of still-life painting, which – as in the above-mentioned case of the “Vanitas” – often presented more than one layer of meaning.

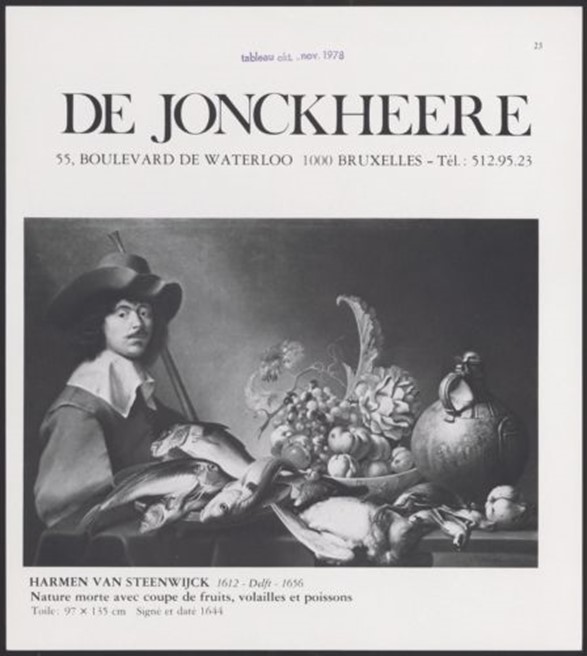

To conclude, while Steenwijck produced primarily small-scale paintings, the ambitious format of the present canvas and its wealth of narrative detail suggest it represented an important commission, stylistically similar to another work by the artist, signed and dated 1644, published in 1978 by the De Jonkheere Gallery (fig. 2).

Provenance

Formerly with John Moncrieff MacMillan, London

Height: 163cm, 5 foot 4 1/2″

Width: 248cm, 8 foot 2″

£POA